La siguiente nota es de esos eventos que me llenan de mucho orgullo y me llena de mucha satisfacción por la transcendencia que representa, para los que no están familiarizados, mi asombro se debe al hecho de que mi nombre figure en Newsweek, los que saben no me dejarán mentir, de ahí ique la nota se encuentre en inglés. – Arturo Bayona.

Fuente original de la nota: https://www.newsweek.com/inside-mexicos-mysterious-bat-cave-blind-deaf-hanging-snakes-1579139

By ANA LACASA, ZENGER NEWS on 3/28/21

Less than 180 miles from Cancun’s spectacular beaches, through a nearly roadless stretch of mosquito-crowded jungle, lies a mysterious dark cave that is home to a species of blind, deaf snakes that feed mainly on flying bats.

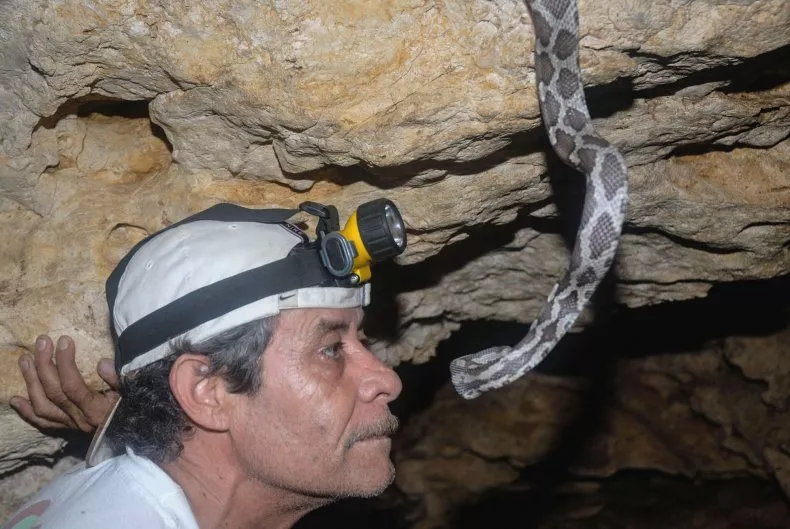

The inky black cave is a unique ecosystem. “This is the only place in the world where this happens,” said Arturo Enrique Bayona Miramontes, the biologist who discovered it. His wandering flashlight beam first discovered the cave and strange animals living inside.

The cave, many miles inland from the famous Mayan ruins of Tulum, is unknown to virtually all tourists and a genuine surprise to scientists. Once again, the Central American jungle has been peeled away to reveal another species, another hidden natural world.

The “cave of the hanging snakes” has a 65-foot wide mouth from which thousands of bats of seven different species swarm out every night, seeking food in and around Lake Chichancanab, some 2 miles away. When the bats return from nighttime feeding, some become food for the snakes.

Carved from rock by rainfall and runoff over millions of years, the cave is carpeted in bat droppings. On the rock ceiling hang untold hundreds of thousands — maybe millions — of bats. And clinging to the cave’s roof among the bats dangle thousands of sightless snakes. When a bat’s wing brushes by, the snake instantly strikes, clamping its prey in its jaws and devouring it.

The technique of the yellow-red rat snake is frighteningly precise, Bayona Miramontes said. “These snakes do not see or hear, but they can feel the vibrations of the bats flying, and they use that opportunity to hunt them with their body, suffocating their victims before gobbling them down.”

The reptiles live in crevices in the cave wall. When a bat is too big to drag inside, the snake expertly breaks its wings.

A Mayan community in Kantemó, a Yucatán peninsula settlement so small that it has only one church, has been protecting the slithery predators’ environment, said Bayona Miramontes.

To protect this unique ecosystem, no more than 10 visitors are allowed inside at a time. No photography is permitted. The Covid-19 pandemic has closed the cave, for now, but it will reopen when the health department of the Mexican state of Quintana Roo allows tourism again.

Bayona Miramontes recalls how he and his assistant made the discovery. “The local community came to the technological institute where I was working in search of alternative ways to approach the jungle in a sustainable way. I was told to conduct a survey of the local cultural, history and water resources in the area to evaluate its resources,” he said.

The villagers showed him a cave that no one ever entered because age-old legends warned of evil spirits living there. Once he obtained permission from local leaders to venture inside, he said, “nobody wanted to accompany me and I went alone, finding a lot of bats and remains of antique pots which were believed to be of Mayan origin. And I saw that it had a huge potential for tourism.”

The biologist and his team had only visited the cave during the day, entirely missing the pitch-black feeding cycle. But during a nighttime bike ride four months later, he and his assistant saw a mass exodus of bats flying out of the opening.

“We decided to go in, and it was a great surprise. … I looked up to the ceiling of the cave and I saw snakes hanging down, some of them moving rhythmically, others with a bat in their mouth, and others with nothing. But it was clear that they were hunting, in total darkness,” Bayona Miramontes said. He said his assistant was scared, but he knew that what they were witnessing “was going to be the discovery of my life” and a good opportunity for the community.

They visited the cave at night for three months. He even slept inside, confirming that the same phenomenon happened when the bats returned from feeding in the jungle.

After making detailed recordings and notes about the phenomenon, he revealed his discovery to the nearby community. They were afraid, he said, because their oral tradition held that the bats could hurt their children. They have decided over time that he was right. “They even want to erect a statue of the snakes, as it has opened up the small community, which does not even appear on any maps, to world tourism,” Bayona Miramontes said.

An ecotourism project now includes bird watching and visits to the lake and the cave, but with a controlled number of people. Bayona Miramontes said deals fell through with tourism agencies that saw little opportunity for profit. But private fundraising has produced enough money to build a visitor center and to train guides.

The snakes are thought to have lived in Kantemó for 200 years or longer, adapting perfectly to the darkness and living in a sort of tense equilibrium with the other animals. The biologist said the cave held three major benefits for the reptiles: “They have a constant temperature all year round. They can find food every day without difficulty, as they only have to hang and wait for the bats. And they are the queens of the ecosystem, as they do not have any natural predators.”

The snakes and bats have company inside their cave, including the blind brotula, a type of transparent eel that has evolved and adapted to the darkness. It’s native to Mexico and the only known species of its kind.

This balanced ecosystem could be threatened by even the smallest of changes in the chemical composition of the water, but there is no danger “as long as the underground water currents keep on going,” Bayona Miramontes said.

To visit the cave, contact Cueva de las Serpientes Colgantes de Kantemó on Facebook.

Fografías por Alberto Friscione