This month, archaeologists in Mexico will begin excavating a secret tunnel thought to lead beneath a pyramid built by the ancient Maya.

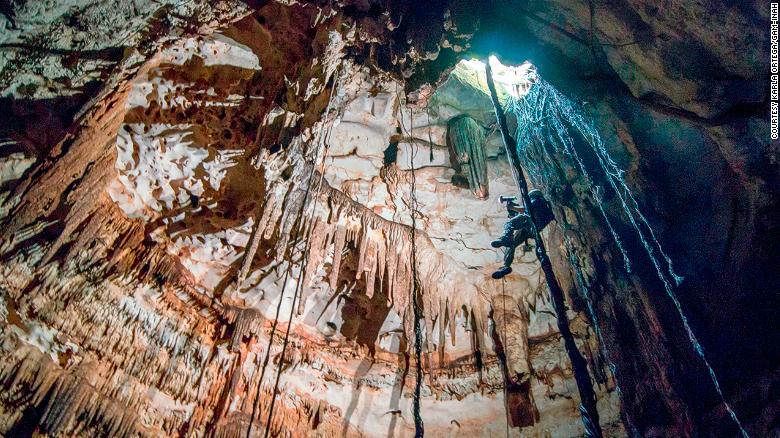

The tunnel was sealed off centuries ago by the Maya, but archaeologists plan to clear it in order to reach a hidden “cenote” — an underwater cavern that was central to Mayan spirituality.

Cenotes are water-filled sinkholes and are the only source of fresh water in Mexico’s Yucatan state. The Mayan civilization could not have survived here without them, but as well as sustaining physical life, these deep caverns were a key part of the Mayan cosmology.

So important were these sites to their beliefs that the Maya practiced human sacrifice here, throwing bodies into their depths in the hope of winning the favor of their fickle rain god, Chac.

Read: 1,500-year-old ruins shed light on mysterious Moche people

“For Mayans, cenotes were the entrance to the underworld,” says Guillermo de Anda, an underwater archaeologist who is leading the team from the Great Mayan Aquifer Project.

“The Maya conceived of the cosmos as having three basic layers: heavens, earth and underworld,” he explains. “The underworld was very important — it was considered the origin of life, and if the Mayans didn’t keep a good balance between this layer of the universe and their own it could mean drought, famine or sickness.

“So they knew they had to keep the peace with their deities of the underworld and this is why sometimes they made offerings.”

Secret cenote

Before the Spanish arrived in Mexico in the 16th century, the Maya people were one of the world’s great civilizations, and the ruined city of Chichen itza, in Yucatan state, is one of their most impressive achievements. Spread out over 4 square miles, it was built around the 5th and 6th centuries AD but mostly abandoned by the time of the Spanish conquest.

Towering over the ruins is a four-sided pyramid known as “El Castillo” — a temple to the feathered snake god Kukulcan, one of the major deities in ancient Mexico. The structure is 79 feet tall (24 meters) and was built according to strict geometric principles. Each side faces one of the cardinal compass directions and has 91 stairs. Combined with the step on the top platform, there are a total of 365 steps — the number of days in the solar year.

Chichen itza has four visible cenotes, but two years ago, Mexican scientist Rene Chavez Segura determined that there is a hidden cenote under El Castillo, which has never been seen by archaeologists.

Now, De Anda’s team — which last month discovered the world’s largest flooded cave — is on the verge of reaching it.

Last November, they explored two underground passageways leading from a smaller pyramid at Chichen Itza, known as the Ossuary. They had hoped the passageways would lead beneath El Castillo, but discovered the Maya had intentionally sealed them off with piles of stone.

“The Maya blocked things a lot,” said de Anda. “In a cave that’s important they seal it forever.”

Forever, or until a group of determined archaeologists comes along.

‘Center of the world?’

The team is returning to the tunnels with the aim of clearing them enough to find an entrance to the cenote under El Castillo. De Anda, a researcher with Mexico’s Institute of Anthropology, believes the excavation will take around three months to complete.

There are known cenotes directly to the north, east, south and west of El Castillo, which de Anda says indicates the settlement pattern is directly related to the natural sacred geography.

He believes the cenote under El Castillo could represent a 5th direction — the “axis mundi” or center of the world, which the Maya depicted as a huge tree, known as The Tree of Life. And it may yield more clues about Mayan beliefs.

‘A message to the water gods’

De Anda says there is still much to learn about the role of human sacrifice in Mayan life.

He has previously analyzed the bones of human sacrifices found in Chichen Itza’s Sacred Cenote and discovered that around 80 percent of the victims were children between the ages of 3 and 11.

“Sometimes it’s hard to understand why they sacrificed children but we have to stop and think about the health status of those children,” he says. “They were a very low stratum of society, maybe children stolen from other communities for sacrifice.”

De Anda says that analysis of the children’s skulls, bones and teeth has revealed that they were in poor health, showing signs of anemia and malnutrition.

“There’s a possibility they were already dead when they were deposited in the cenote, and maybe they honored them by putting them there, or maybe they were trying to send their spirit to send a message to the water gods.”

But he admits, “to get to the truth we still need to do a lot of research.”

Fuente: https://edition.cnn.com/2018/02/02/world/chichen-itza-maya-tunnel-cenote/index.html